Data File Formats

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

What are the common file formats for Climate Datasets?

What is NetCDF?

How can we open and access data in NetCDF files?

Objectives

Become familiar with some of the varieties of data formats used for climate data

Learn how to peruse and parse a NetCDF file

Introduction to

xarray

Formats of Datasets

There are many data formats in use in the field of climate research, but there are a few that predominate:

-

NetCDF: The Network Common Data Form (originally called the Network Climate Data Format). Typical suffixes:

.nc,.nc4. This binary format was developed by the climate community, but has been adopted in many other communities due to its utility and self-describing format (i.e., the data file also includes metadata to describe the contents, its spatial, temporal and any other dimensions, properties and attributes). Beginning with version 4, data compression has become an option. It has become the most common format for climate data files. -

GRIB: GRIdded Binary format. Typical suffix:

grb. GRIB was developed by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) as an efficient compressed binary format for exchange of weather data. The original format (GRIB1) is only semi-self describing, as it required external look-up tables to decode indices used. GRIB2 is truly self describing. Unlike NetCDF, GRIB allows for tailored compression for each variable in a file. -

Flat binary files, including those produced as output from FORTRAN programs, and the data files produced by GrADS. No standard suffix. Flat binary files contain no metadata, and usually cannot be understood without additional documntation. The native GrADS file format pairs one or more flat binary data files with a “data descriptor file”, usually ending with the suffix

.ctl, that contains all the metadata of a dataset in a human writable and readible form. -

ASCII files, which include

.csvor “comma separated values” files, which are a simple form of storing spreadsheets. ASCII stands for “American Standard Code for Information Interchange”, and is the text or “string” format standard for many programming languages. ASCII is considered easy to read by humans, but is much less efficient at storing data than binary formats. It is advisable only for small files. -

Excel files, a spreadsheet format with a wide range of specialized formatting extensions from Microsoft. Typical suffixes:

.xls',.xlsx` (the latter uses extensible markup language XML to encode metadata information). -

GIS (Geographic Information System) files come in a variety of different formats depending on the application and software used. Often information for a single dataset is split into multiple files, particularly for “shapefiles” containing polygonal data.

-

Orthorectified Imagery Formats such as

.tifffiles are binary image files used to store geo-located data (also often with metadata in separate files), common for some observational data, especially imagery-derived data from remote sensing or aircraft.

In this course, we will focus on the top part of this list, but know that Python has libraries available to read all these and many more dataset formats.

NetCDF

NetCDF has a software library called NCO (netCDF Operators) that, independent of Python or any other software,

can perform a variety of operations on NetCDF datasets.

The NCO executables (each function acts like its own Unix command with options and arguments - they even have man and info pages)

can be very handy for doing basic operations on data in the bash shell on a Unix system, such as compressing

(or “deflating” in NetCDF-speak) a large uncompressed NetCDF dataset you downloaded, in order to conserve disk space.

Perhaps the most useful and often used NCO command is ncdump. Without options, it will dump the entire contents of a NetCDF file to the screen as

ASCII numbers and text. The -h option shows only “header” information and not the contents of variables, basically showing you only the metadata.

Returning to that data file you downloaded to your scratch directory… give it a try:

$ ncdump -h sst.mon.ltm.1981-2010.nc

A lot of text is sent to your screen, starting with a list of the dimensions of the dataset in the file, then the

variables including a listing of the attributes of each variable, and finally the attributes of the dataset itself (global attributes).

NetCDF metadata

The

ncdump -hcommand lists metadata in a human-readable format that is fairly easy to interpret.Find the following information:

- The names of the dimension variables in the dataset and the size of each

- The meaning of each dimension variable

- The data variables (the ones that vary in both space and time dimensions)

- What is this a dataset of? (peruse the “global attributes”)

Solution

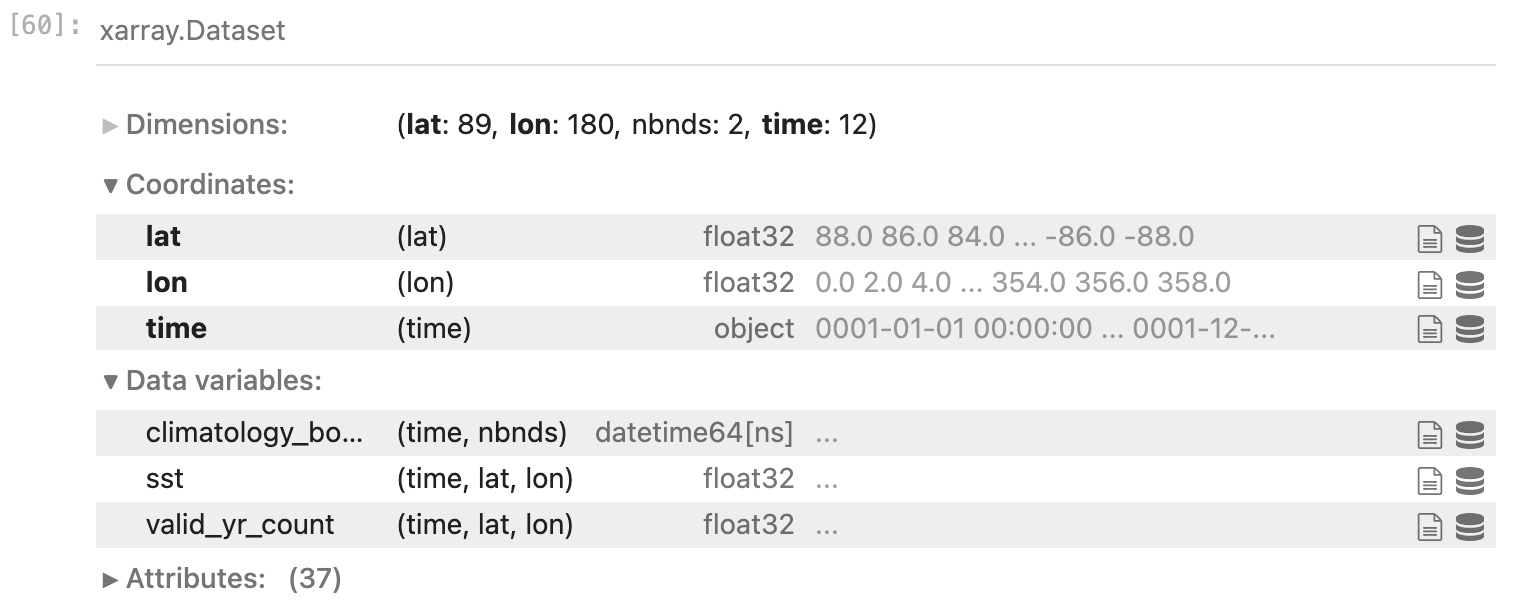

- lon = 180; lat = 89; time = 12; nbnds = 2

- lon is longitude (˚E); lat is latitude (˚N); time is months (although that is not terribly obvious from the metadata); nbnds is time boundaries (also a bit mysterious at this point)

- sst is sea surface temperature [˚C]; valid_yr_count is the “count of non-missing values used in mean”, i.e., number of years of good data used.

- A monthly SST climatology averaged over 1971-2010 combining several sources of data. It’s called “NOAA Extended Reconstructed SST V5” and there is J. Climate paper describing it.

There are other useful software libraries similar to NCO. In particular, there is the Climate Data Operators (CDO) software package that has much of the same functionality as NCO, but also works with other data formats such as GRIB.

Introduction to xarray

To open and use NetCDF datasets in Python, we will use the xarray module.

xarray allows for the opening, manipulating and parsing of multi-dimensional datasets that include one or more variables and their associated metadata.

In particular, xarray is built with the dask parallel computing library that scales and vectorizes operations on large datasets, making calculations fast and efficient.

It provides a very nice balance between ease-of-use and efficiency when analyzing climate datasets.

Open a new Jupyter Notebook (name it something like “Plot_netcdf.ipynb”) and in the first code cell, type the following three import statements

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import xarray as xr

Note: there is nothing special about the choice of these abbreviations for these three modules - but they happen to be the most commonly used ones by most people. You could use any abbreviation you like, or none at all.

In a new cell, let’s define the path to the dataset we downloaded and open it with xarray:

file = "/scratch/<your_username>/sst.mon.ltm.1981-2010.nc"

ds = xr.open_dataset(file)

Now query the object name ds by typing its name and <return>:

ds

You will get something that looks much like the result of ncdump -h, but even more helpful.

You will also be able to view the contents of any variable, and expand/contract a view of any attributes.

For very large or multi-file datasets (xr.open_mfdataset() can open multiple files at once and link them together in a single object),

You will also be shown how the data are “chunked” - i.e., organized when loaded into computer memory.

Next, let’s make a plot of the data. To access the variable sst in ds, we can either say:

ds.sst

…or…

ds['sst']

The latter is more flexible and also makes it clear that ds is not a module with a function called sst – it is less confusing for a human to read.

You can see that the dump of ds['sst'] shows more focused information, and a sample of the data in the arrays.

There are 3 dimensions: time, latitude and longitude (in that sequence - the sequence is important!).

To make a 2-D plot, we will choose the first (0th) time step:

plt.contourf(ds['sst'][0,:,:])

Things to note:

contourfis one of the many plotting funtions of matplotlib.pyplot, and especially good for plotting gridded environmental data.- The

[0,:,:]contruct tells what to do with each dimension ofds['sst']in order: [time,lat,lon].- An integer (or variable containing an integer) specifies one index value for that dimension.

- A : by itself means the entire range.

- Sub-ranges are specified with a mix of integers and colons, e.g.:

1:means all but the 0th element,2:5would include elements 2-4 (remember it is “up to but not including” the last number). - A second colon could be used to indicate the step, e.g., :10:2 would include elements 0,2,4,6,8 (but not 10).

- The map is upside down! That is because although there are latitudes and longitudes associated with the last two dimensions of the array, we did not convey that information to the plotting function. Thus, it treats it like a mathematical array with the origin at the lower left. We can also see that the axes are labeled by the indices and not latitudes and longitudes.

We could flip the plot over by changing the indexing of the latitude dimension:

plt.contourf(ds['sst'][0,-1::-1,:])

What does that indexing mean?

- The first

-1means the last element in the latitude dimension. Negative indices are a shortcut to counting from the back instead of the front. The next-to-last element would be -2, etc. - The second

-1is the step.-1::-1means start at the back and count toward the front (in this case, start in the south and count north) by ones.

The question mark, and

<tab><tab>In Python, and particularly in Jupyter Notebooks, there are many sources of help as you are writing code. Two that are especially useful:

- If you place a question mark immediately after an object (Python is an “object-oriented” programming language, and everything in Python is an “object”), in most cases you will get a brief, helpful description of it. The degree of detail will vary, but it can help you to keep straight and understand what is what.

- If you are typing the name of a function and halfway through you don’t quite remember the spelling or syntax, you can hit the tab twice

and a list of auto-complete options will come up to help you. You can click on the one you want to finish typing it.

Key Points

NetCDF is now the most common climate data format.

xarraywants to be your best friend - let it!